The Integrated Motivational-Volitional (IMV) Model of Suicidal Behaviour

The Integrated Motivational-Volitional Model of Suicidal Behaviour was first proposed in 2011 by Rory O’Connor (IMV; O’Connor, 2011) and it was refined in 2018 (O’Connor & Kirtley, 2018). Its aim was to synthesize, distil, and extend our knowledge and understanding of why people die by suicide, with a particular focus on the psychology of the suicidal mind. The model was developed from the recognition that suicide is characterized by a complex interplay of biology, psychology, environment, and culture (O’Connor, 2011), and that we need to move beyond psychiatric categories if we are to further understand the causes of suicidal malaise. Many theoretical models have adopted too narrow a focus; this model built upon and extended the growing empirical evidence base that had been accrued across the international research literature. It also highlighted a pertinent challenge within the field of suicidology; the ability to better identify not only who will develop suicidal thoughts (or not), but who will act on these thoughts and when. Indeed, this is a central premise of the model: the factors associated with the development of suicidal ideation/intent are distinct from those that govern the transition from suicidal ideation to suicide attempts/suicide.

Recommended citation for the IMV model:

O’Connor, R. C. & Kirtley, O. J. (2018). The Integrated Motivational-Volitional Model of Suicidal Behaviour. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 373:20170268. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2017.0268

Below is a brief podcast from Rory O’Connor describing the IMV model to accompany the O’Connor & Kirtley (2018) Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B publication.

In brief

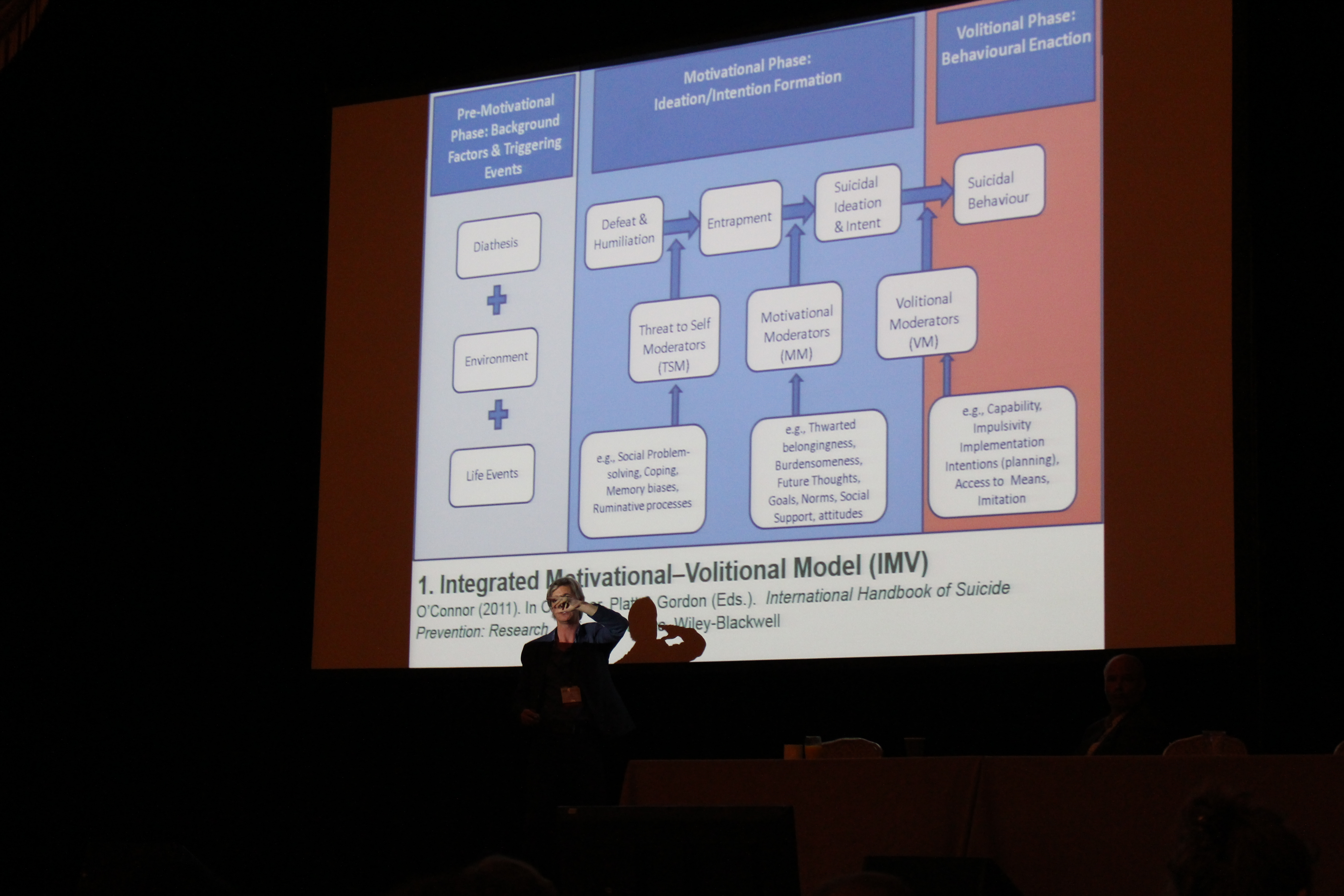

In brief, the IMV is a tripartite model that proposes that suicidal behaviour results from a complex interplay of factors, the proximal predictor of which is one’s intention to engage in suicidal behaviour. Intention, in turn, is determined by feelings of entrapment where suicidal behaviour is seen as the salient solution to life circumstances. These feelings of being trapped are triggered by defeat/humiliation appraisals, which are often associated with chronic or acute stressors. The transitions from the defeat/humiliation stage to entrapment, from entrapment to suicidal ideation/intent, and from ideation/intent to suicidal behaviour are determined by stage-specific moderators (i.e., factors that facilitate/obstruct movement between stages). In addition, background factors (e.g., deprivation, vulnerabilities) and life events (e.g., relationship crisis), which comprise the pre-motivational phase (i.e., before the commencement of ideation formation), provide the broader biosocial context for suicide. In essence, the three parts of the model could be summarised as follows: (1) Background Factors (Pre-motivational phase; the context in which suicide may occur), (2) Development of Suicidal Thoughts (Motivational phase; how/why suicidal thinking emerges) and (3) Attempting Suicide (Volitional Phase; factors associated with acting upon one’s thoughts of suicide).

More details about the development of the model can be found in the 1st edition of the International Handbook of Suicide Prevention and in a 2011 editorial about the model in the journal Crisis. For some more information on the development of the IMV, double click here and here for two brief YouTube videos. An updated chapter describing more information about the IMV model (up to 2016) can be found in the 2nd edition of the International Handbook of Suicide Prevention.

2018 Refinements of IMV model (O’Connor & Kirtley, 2018)

Three important refinements of the IMV model were published in 2018 (O’Connor & Kirtley, 2018). First, in recognition of the potential cyclical nature of the suicidal ideation–attempts–ideation relationship, we have added this to IMV model (see dotted lines in Figure 1 above and Figure 2 below). What is more, if an individual has already made a suicide attempt, it is unlikely that the process of ideation and intention formation for a repeat suicide attempt will begin anew and manifest in the same way as for a first episode of suicidal behaviour. Second, as summarised in Figure 2 below, we have further specified the volitional phase by describing 8 key volitional moderators.

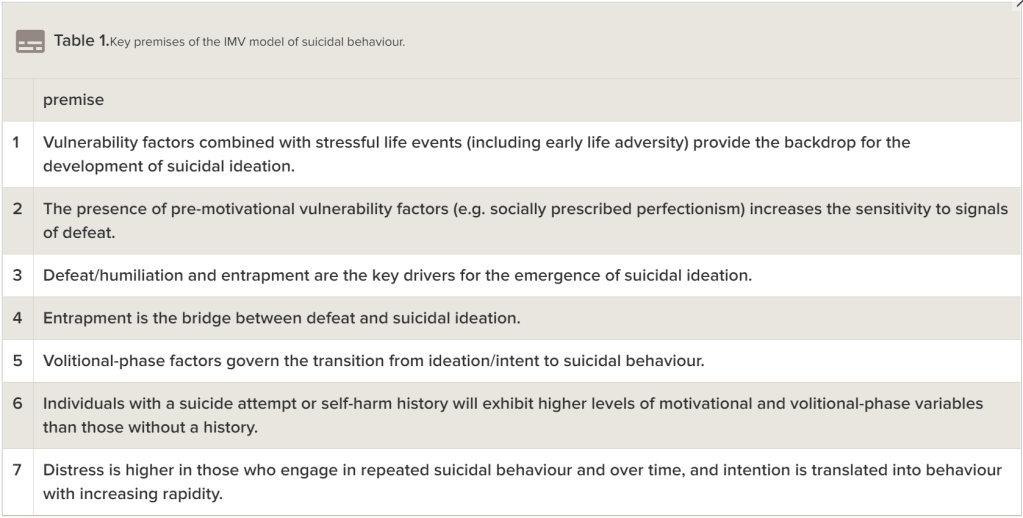

Third, we have now specified seven key premises underpinning the IMV model which are outlined in Table 1 below.

Applying The Model

One of the strengths of this theoretical framework is that it generates testable hypotheses, which in turn, if supported, point to opportunities for potential intervention. Different aspects of the model have already been tested, yielding a number of encouraging findings (we focus on research involving members of our lab here):

For example, in one study conducted by our research group we investigated whether entrapment was a proximal predictor of repetition of suicidal behaviour over time. The short answer was yes. Whereas, suicidal ideation, past suicidal behaviour, depression, hopelessness, defeat and entrapment were each univariate predictors of suicide attempt over the subsequent 4 years, entrapment was the only modifiable predictor (alongside previous suicide attempts) in multivariate analyses. Although these findings are encouraging, it will be good to replicate these in a larger sample (O’Connor, Smyth, Ferguson, Ryan & Williams, 2013). Double click here for a brief video description of the study. See also O’Connor & Portzky (2018) where we synthesise the latest evidence on the entrapment-suicide risk relationship.

The model also makes important predictions about the factors which are most important in distinguishing between those who think about suicide (but do not attempt suicide) and those who attempt suicide/die by suicide. Indeed, in a recent large-scale study we demonstrated that, as predicted by the IMV model, volitional moderators (included exposure to suicide, impulsivity, fearlessness about death) were the most important factors in differentiating between these two groups (Dhingra, Boduszek & O’Connor, 2015). A structural test of the model has also been published (Dhingra, Boduszek, & O’Connor, 2016). More recently, using data from the Scottish Wellbeing Study, a national study of 3,508 young people in Scotland, we found more evidence for the utility of volitional phase factors in distinguishing between those who had thought about suicide and those who had attempted suicide (Wetherall et al., 2018). The importance of exposure to the suicidal behaviour of others in behavioural enaction was also reinforced in a large population-based birth cohort study (Mars et al., 2018).

We have also looked at different components of the motivational phase of the model. For example, across a range of studies we have shown that impaired positive future thinking is a key factor within the suicidal process (e.g., Hunter & O’Connor, 2003; O’Connor et al., 2000; O’Connor et al., 2004). Indeed, in a clinical study of patients with a history of repeat self-harm, impaired positive future thinking was a better predictor of suicidal ideation 2-3 months following a self-harm episode than global hopelessness (O’Connor et al., 2008). Particular aspects of positive future thinking are also associated with hospital-treated self-harm over time (O’Connor et al., 2015). We have also looked at goal regulation – another motivational moderator – and found that the way in which we respond to unachievable goals predicts repetition of self-harm/suicide (O’Connor, Ryan, O’Carroll, & Smyth, 2012, O’Connor et al., 2009). There is also new evidence that resilience may buffer the entrapment – suicidal ideation relationship (Wetherall et al., 2017).

Although the IMV model was developed with suicidal ideation and behaviour in mind, the central tenets of the model can also be applied to self-harm irrespective of levels of suicidal intent. By way of illustration, in a recent study of 5,604 adolescents, as predicted by the IMV, we found that motivational phase and pre-motivational phase personality variables did not distinguish between adolescents who seriously thought about self-harm but never acted on their thoughts (i.e., ideators-only) and those who actually engaged in self-harm (i.e., enactors), whereas the volitional phase variables did (O’Connor, Rasmussen, & Hawton, 2011). In health psychological terms, we would argue that the presence of volitional moderators makes self-harm more likely because they bridge the intention-behaviour gap.

The IMV model has also recently been used to inform the development of interventions. Specifically, with colleagues, we have developed a volitional help sheet (VHS, see implementation-intentions in the volitional phase of the model) and investigated its utility in reducing suicidality and self-harm. The VHS is a brief intervention tool (to be used as an adjunct to usual care) which encourages participants to think about critical situations when they are tempted to self-harm and to consider alternative solutions. The findings of the first exploratory study in Malaysia have been promising (Armitage, Abdul Rahim, Rowe & O’Connor, 2016, although conclusions limited by attrition & self-report outcomes) and a second large scale RCT has also yielded encouraging findings among those with a previous history of self-harm hospitalisation over 6 months (O’Connor, Ferguson, Scott, Smyth, McDaid, Park, Beautrais, & Armitage, 2017). We are also currently conducting a safety planning (volitional phase target) and telephone support feasibility RCT (Safetel) with people following a suicide attempt. The study details are summarised on Youtube here, the trial registration is here and the protocol will be published soon.

Systematic reviews

Two systematic reviews have been published recently which synthesise some of the extant evidence on the IMV model (Souza et al., 2024, Winstone et al., 2024). The Souza et al. (2024) review summarises the evidence from 100 studies that have tested different pathways within the IMV model. Whereas Winstone and colleagues (2014) critiqued 53 studies which had assessed 15 IMV constructs using ecological momentary asssessment (EMA) techniques.

Self-harm and suicide prevention competence frameworks

The IMV model informed the recently published National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health self-harm and suicide prevention competence frameworks for work with adults and older adults and for work with children and young people. These frameworks were designed to support the development of training curricula for practitioners from a wide range of clinical and professional backgrounds, to evaluate training/existing services and to reflect upon individual professional practice.

Specifically, understanding the motivational (including the importance of entrapment) and volitional phases of suicide risk is included in the competence frameworks. Taken directly from the IMV model, these are core aspects of the ‘Understanding self-harm and suicidal ideation and behaviour’ competence in both the adult and children and young people competency maps. We believe that an understanding of the IMV model and its applications in clinical and non-clinical settings should form the basis for all self-harm/suicide prevention training programmes.

The Way Forward

The model is relatively new, therefore it requires further empirical examination. In the figures above, the dominant pathways are outlined and are directly testable. To this end, we, and other groups nationally and internationally, are currently testing different components of the model and we will report these findings in the years ahead. For example, we are working with colleagues in the Netherlands (Nuij et al., 2018) to investigate the utility of daily self-monitoring (of factors derived from the IMV model) via ecological momentary assessment and mobile safety planning in the treatment of those who are suicidal. We are also employing new statistical techniques, like network analysis, to investigate the complex relationship between different IMV-related risk and protective factors (deBeurs, van Borkulo & O’Connor, 2017).

The systematic study of the mechanisms underpinning suicide is important not only to advance theory but it is also vital for the development of evidence-informed interventions. The latter will have a much greater chance of success if the potential mechanisms which underpin their effects are better understood. Their success will also be determined by recognising that a ‘one size fits all’ approach will not be successful and that theoretically-informed research will help unpack what works for whom, when and where.

And Finally…

The Mental Elf website published an independent blog (written by Alexandra Pitman and Lisa Marzano) about the Integrated Motivational-Volitional Model of Suicidal Behaviour on World Suicide Prevention Day 2018.

It’s available to read in full here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.